When I started in my current role, no one warned me that 80% of the job would be repeating myself.

I thought it would be coaching. Teaching. Creating structure. And it is. On paper. But in practice? It’s standing in front of a different group of people every day, saying the same things in slightly different ways, hoping that this time it lands.

I train small groups. Sometimes just one person. Sometimes eight or nine. I walk them through the same material, safety standards, expectations, critical procedures. The content doesn’t change, but the people do. Which means every delivery has to adapt.

What clicked for the group yesterday won’t work today.

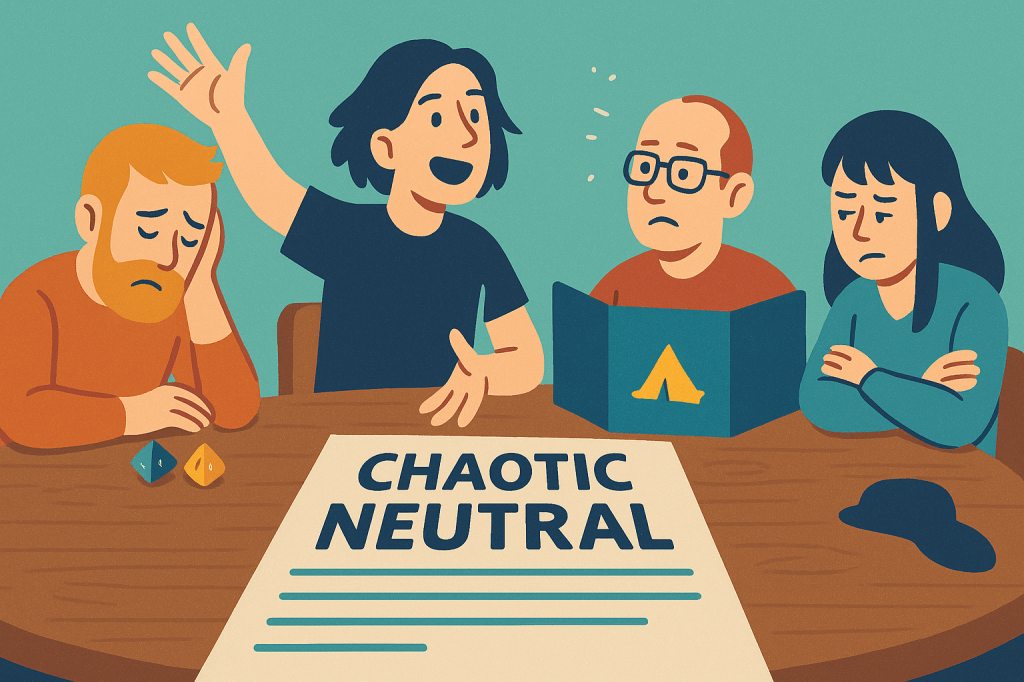

The guy in the back row who’s been a driver for 10 years and thinks he’s seen it all? He needs to hear things in a way that doesn’t make him feel talked down to.

The nervous new hire who’s scared of reversing in a windowless van? They need clarity without pressure.

And the person who’s been half-listening because they think they’ve already passed everything? They’re the one that’s going to miss a critical detail and then say, “No one ever told me that.”

So you repeat yourself.

You find new metaphors. You switch up the tone. You test your own patience. And when someone asks a question you just answered, you don’t snap. You repeat it again, because your job isn’t to feel heard, it’s to be understood.

That’s the deal when you lead small groups. You’re not giving a TED Talk. You’re creating moments of clarity in a sea of distractions, nerves, and assumptions. That takes more than a slide deck.

It takes presence. Patience. And an understanding that you’re not failing when you have to repeat yourself. You’re doing the job right.

The day I really understood that was the day a trainee told me, “I don’t know why, but when you said it, it finally made sense.”

It wasn’t magic. It was iteration.

And yeah, by that point, I’d said it 400 times.