There’s a particular kind of emotional exhaustion that settles in when your Game Master thinks being in charge means being right all the time. It starts slow–your character’s little backstory never gets acknowledged, your clever ideas get waved off with a smirk and a house rule, and pretty soon you’re just rolling dice and getting your turn over with as little friction as possible. You used to be excited to play. Now you’re mostly just tracking hit points and trying to survive the session. It’s not that you don’t like the game. It’s that the person running it has made the table feel like a minefield.

I’ve had day jobs that feel exactly like that.

What I call Negative Leadership shows up in real life the same way it shows up in bad tabletop campaigns. It’s not always loud or theatrical. It’s a mindset. A controlling, defensive, brittle approach to being in charge. It’s the manager who talks like a GM who’s memorized every line of the module but hasn’t noticed that half the players are disengaged. They think “leadership” means quoting the rulebook and punishing deviation. They treat innovation like it’s cheating and feedback like it’s a charisma check they can refuse.

I’ve worked across a bunch of different environments–logistics, operations, customer service–and while the industries changed, the vibe of a bad manager never did. You try to bring something to the table, and they act like you’re violating canon. I once stayed late to help a new hire finish up a shipment–just helping out. Next day, I get pulled aside for “disrupting the process.” In another job, a manager pinned dollar bills to his office wall from bets he won against his own staff, like we were all stuck in some sad, corporate version of Tomb of Horrors. Nobody said anything, but we all saw the message: this place runs on ego checks.

What makes it harder is that most of these leaders don’t see themselves as the problem. They think they’re enforcing standards. That they’re the only thing holding back the chaos. But treating your team like a bunch of unruly NPCs doesn’t build order–it builds resentment. Calling someone “not great with people” doesn’t begin to cover it. It’s more like they see empathy as a homebrew mechanic they don’t trust.

Frederick Herzberg’s Motivation-Hygiene Theory puts a fine point on it: the stuff that demotivates people isn’t the same stuff that inspires them. You can have health benefits, free snacks, and an end-of-week XP bonus, but if your boss treats you like a barely tolerated raccoon who wandered into the breakroom–something to be monitored and controlled–you’re not going to stay motivated. You’ll stick around, maybe, but your heart won’t be in it. It’s like showing up to a dungeon crawl where the GM never lets you explore. You’re not playing–you’re just rolling to comply.

And like any bad GM, the truly corrosive managers rarely blow up in obvious ways. It’s not all dramatic yelling or slamming doors. It’s a slow bleed: a joke that lands too hard, a change in protocol with no explanation, a public correction that wasn’t necessary. I once got called out for parking a training vehicle “the wrong way,” even though it was the safest available option. The response wasn’t, “Let’s talk through it.” It was, “Rules are rules.” No context, no conversation. Just pure authoritarian DM energy.

Douglas McGregor’s Theory X and Theory Y explains this kind of behavior. Theory X leaders believe that people are fundamentally lazy and need to be coerced into productivity. So they act like GMs who run every session like a power fantasy–one where players can’t be trusted to make good decisions, so every path is railroaded and every choice is an illusion. And when the team stops engaging, these managers see it as proof. “See? They only work when I’m watching.” Yes, because you’ve made watching feel like surveillance, not support.

The wild part is, I came into all those jobs wanting to contribute. I had ideas. I saw things that could be improved. I wanted to play the game well, not break it. But when your every move gets treated like a challenge to the GM’s authority, you eventually just stop rolling. Not because you don’t care, but because the consequences for trying feel too steep.

The worst leadership I’ve experienced didn’t look dramatic. It looked polite. Measured. Controlled. And deeply suffocating. You could ask questions, sure–but only once. And only if they were easy. The mood in the room said: Don’t make waves. It’s the difference between a campaign where the players feel powerful and one where they feel watched. Some leaders don’t know the difference.

What makes it worse is that these kinds of leaders often believe they’re respected. What they’re actually seeing is compliance dressed up as loyalty. It’s players nodding at the table because they’ve learned what happens if they don’t. Google’s Project Aristotle found that the most successful teams aren’t built on competence alone. They’re built on psychological safety–on people knowing they can speak up without getting wrecked by an attack of opportunity. Negative Leadership squashes that before the first session’s even over.

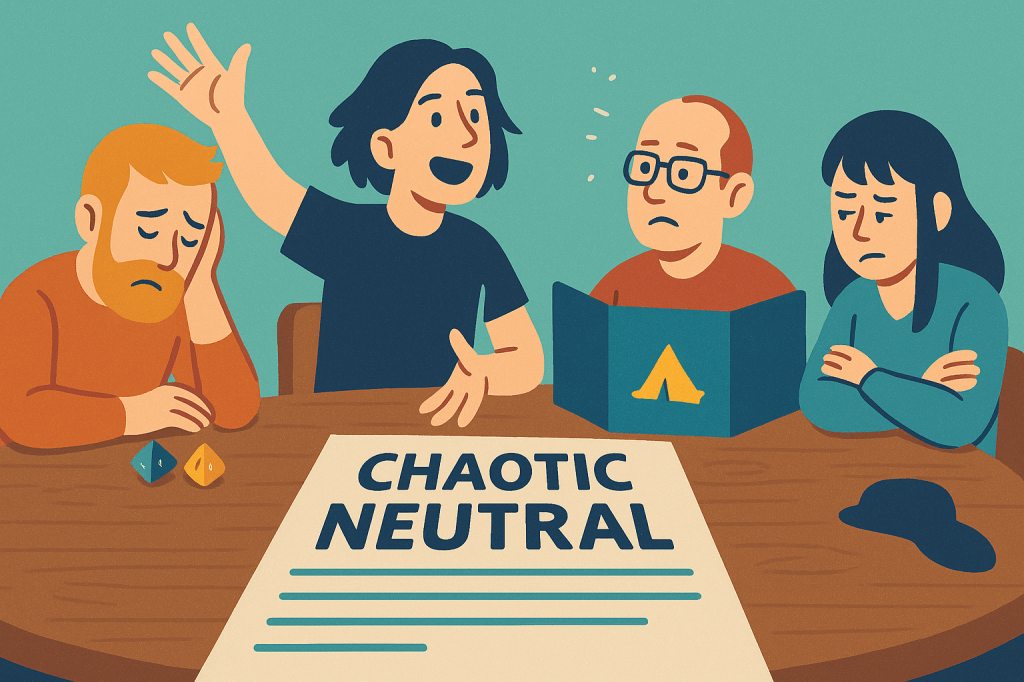

So what’s the fix? It’s not handing over the GM screen to chaos. It’s leading like someone who actually wants the party to succeed. Bernard Bass called this transformational leadership: building people up, not boxing them in. Sharing the story. Listening to the table. Trusting your team to be more than background flavor.

And here’s the kicker–any of us can drift into Negative Leadership if we’re not careful. All it takes is a little pressure, a little stress, and a little too much certainty. Suddenly, you’re making decisions to protect your own authority instead of supporting the people at the table. You’re no longer the GM guiding the story–you’re the final boss in someone else’s burnout narrative.

Leadership isn’t about being the smartest person in the room or holding the most lore. It’s about making the session better because you were there. If people feel freer, braver, and more creative when you’re gone, you’re not leading–you’re just running a game they can’t wait to finish.

And no one brags about surviving that campaign.