Why subtle sabotage isn’t leadership—at the table or in the office.

The first time I heard the term “quiet cutting,” I assumed it was slang for trying to open a bag of chips at a funeral. But no—it’s the latest euphemism for a corporate maneuver where companies avoid the legal, financial, or emotional mess of layoffs by reassigning employees to different roles, usually ones they didn’t ask for, often ones that feel like a punishment. The employee is still on the payroll, technically, but the new job is so mismatched, irrelevant, or isolating that the underlying message is clear: we’d prefer you find your own way out.

For those of us who’ve spent any time leading tabletop roleplaying games like Dungeons & Dragons, it’s hard not to hear that and think of a very specific moment at the game table. A moment when a player becomes such a problem—or maybe just such a nuisance—that instead of having an honest conversation, the Game Master starts passively undermining their character. Not openly. Not with any discussion. Just a steady campaign of quiet obstruction. Their magic “doesn’t work.” Their dice rolls fail in suspicious clusters. The world itself seems to bend around them in increasingly hostile and uncooperative ways.

If that sounds familiar, that’s because the same dysfunction infects both spaces. Quiet cutting in the workplace and passive-aggressive GMing at the table are two heads on the same passive, responsibility-dodging hydra. In both cases, the person in charge wants someone gone—but not enough to confront them. Instead, they engineer an exit by slowly removing power, relevance, and dignity, then shrugging and acting like it was inevitable.

Let’s talk about why that isn’t just bad management or bad game mastering. It’s bad leadership. And if your goal is to become a better GM, a stronger team leader, then this particular pitfall is worth studying.

Quiet Cutting 101: When HR Becomes a Boss Fight

In corporate speak, quiet cutting is framed as “realignment” or “talent optimization.” The company assigns you a new title, a different department, maybe a reduced schedule—and counts on you to quit so they don’t have to pay severance or take a reputational hit. You’re told it’s not a demotion, but you no longer have direct reports. You’re told it’s not punishment, but you’ve been relocated to a dead-end project with no future. It’s not technically unemployment, but it is emotionally exhausting, and most people burn out long before their final paycheck.

Companies that use this tactic often justify it under the guise of strategic planning. But underneath that thin corporate gloss is a fear of direct leadership. Firing someone means confronting performance, having tough conversations, and documenting decisions. Quiet cutting offers the illusion of conflict avoidance—but all it really does is bury the conflict underground where it festers.

It’s worth noting that this isn’t a fringe practice. The Wall Street Journal and Forbes have both reported on its rise, especially as companies look for budget cuts without taking public heat. And it mirrors a well-documented leadership pattern known as passive management-by-exception, a transactional model where the leader only intervenes when something goes wrong, usually in the form of punishment or silent correction.¹

If you’ve ever been on the receiving end of it, you know how demoralizing it feels. If you’ve used it, you may have told yourself you were just “dealing with a difficult person.” But in reality, you were reshaping their world to push them out without having the courage to say so.

The GM’s Version: Nerfing the Character Until the Player Leaves

Now let’s move to the tabletop. A Game Master doesn’t have the option of moving a player to a new department. The party is the party. There’s no off-screen filing cabinet for problem characters. So when a GM grows tired of a player—maybe they argue too much, derail the plot, or just make the game less fun—they may quietly start closing doors.

Instead of telling the player what’s wrong, the GM tightens the narrative screws. Their special skills mysteriously stop working. NPCs stop responding to them. The gods they worship suddenly go silent. Or the GM introduces a recurring mechanic explicitly designed to punish one player’s playstyle—say, a magical field that somehow only seems to affect the chaotic neutral bard.

In some cases, this is subtle and accidental. The GM is frustrated but unsure how to confront it, so they let the story do the dirty work. In other cases, it’s completely intentional. I’ve even heard of GMs who build entire arcs around divine retribution for a player’s misbehavior—not as story, but as out-of-game correction disguised as lore. And again, this isn’t always wrong. Sometimes an in-world punishment is the appropriate consequence for a player who’s gone rogue, especially if it’s discussed and agreed upon as a way to preserve the game.

But the difference lies in how it’s done and why. If you’re using narrative constraints to facilitate a shared storytelling moment with a player who understands the stakes, that’s excellent GMing. If you’re using them to exile a player from the story without having to look them in the eye and say “this isn’t working,” then you’re not leading. You’re ghosting them through game mechanics.

And let’s be clear: your players can feel it. Just like an employee knows when their new “special projects role” is a padded cell with a whiteboard, a player knows when their rogue has become invisible—not in the good way.

What Ethical and Transformational Leadership Have to Say

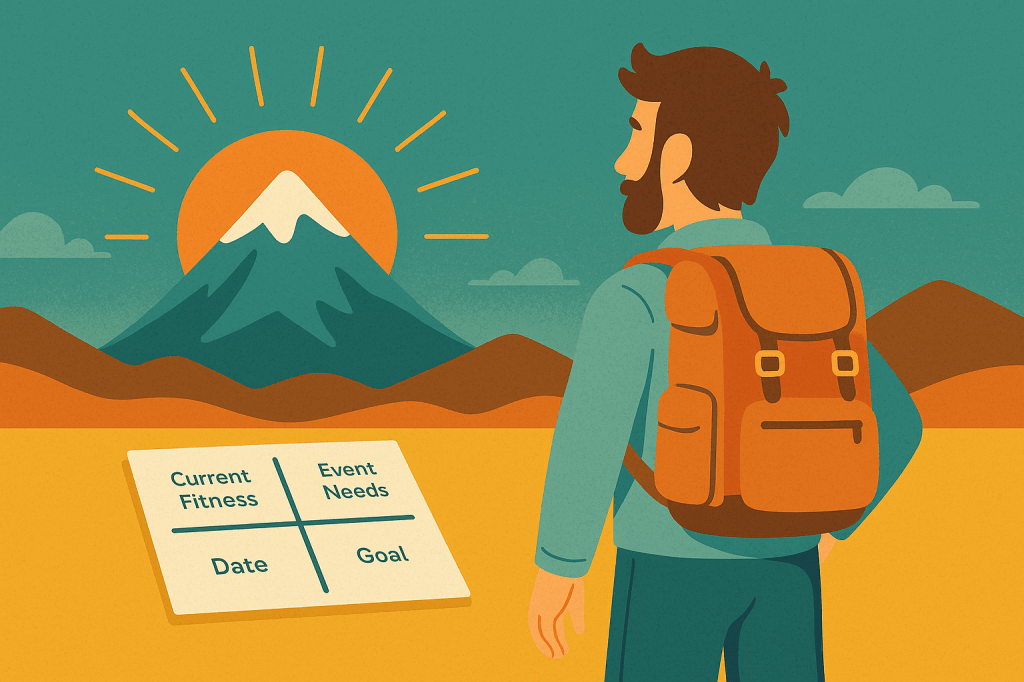

Ethical leadership, as defined by Brown and Treviño (2006), involves fairness, transparency, and moral guidance.² It’s not just about being nice—it’s about being principled, especially when it’s hard. That means talking to people about what’s wrong. It means giving feedback that’s honest, specific, and actionable. It means recognizing when a relationship—whether at the table or in the office—has veered off course and trying to correct it together.

Transformational leadership goes a step further. It asks you to engage people’s potential.³ To see their capacity for growth, not just their current flaws. In a campaign, that might mean helping a player find a new way to contribute, instead of punishing their current choices. In the workplace, it might mean coaching instead of cutting—unless you’ve truly reached the end of the road, in which case it means saying so directly.

This is exactly the kind of material I cover in my RPG leadership workshop, where we examine how the dynamics at a gaming table mirror the power structures of a real team. GMs and managers face the same central challenge: how do you guide a diverse, unpredictable group toward a shared goal without falling into manipulation or avoidance? How do you inspire performance without relying on control? And when things go wrong—as they always do—how do you lead with integrity?

These aren’t just game design questions. They’re leadership questions. And they’re the foundation of both my upcoming RPG leadership book and the DM coaching sessions I offer for aspiring or struggling GMs.

The Fix: Lead Like You’re Being Watched by a Paladin

The solution is simple, but not easy: have the conversation. If someone’s behavior—at the table or on the clock—is disruptive, say so. If a player’s character doesn’t work with the party, talk to them about adjustments. If an employee is underperforming or creating conflict, address it directly. Don’t use silence as a substitute for action. Don’t let the system do your dirty work.

Because whether you’re running a corporate team or a Friday night campaign, the people who follow you deserve clarity. They deserve honesty. And if you can’t give them that, you’re not leading. You’re just rearranging chairs while the ship drifts off course.

So the next time you’re tempted to nerf someone into oblivion or quietly shuffle them out of view, ask yourself: am I avoiding a confrontation, or am I avoiding growth? Because in leadership—as in gaming—what you don’t say often speaks louder than what you do.

Sources

¹ Bass, B. M., & Avolio, B. J. (1994). Improving organizational effectiveness through transformational leadership. Sage.

² Brown, M. E., & Treviño, L. K. (2006). Ethical leadership: A review and future directions. The Leadership Quarterly, 17(6), 595–616. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.leaqua.2006.10.004

³ Northouse, P. G. (2021). Leadership: Theory and practice (9th ed.). Sage.