One of the first things I tell every new hire class is that they should ask as many questions as they want, and they should never feel weird about it. I explain that when they do, one of three things is going to happen. The first is that I’ll just give them the answer. I’ve been doing this long enough that sometimes I know the thing they’re asking about, and I’ll just give it to them straight. The second is that I’ll give them my best guess. I’ll say something like, In my experience, usually the best practice is this…” or “Here’s what most people in the industry do.” And the third is that I’ll tell them who else to talk to–because sometimes I’m not the right person to answer it. Maybe it’s a technical question with the app or some strange behavior with the hardware, in which case, a seasoned veteran out there actually doing the job in the wild is the best resource. But I’m never going to bluff or fake it. Not because I’m some sort of saint, but because I’ve worked under those kinds of people before. The ones who fake their way through every question, who have to be right all the time, who treat leadership like it’s just being the biggest brain in the room. And I’ve seen how much damage that mindset causes.

For some reason, a lot of us go into leadership thinking our job is to have all the answers. That’s the myth we’ve been sold. That the leader is the one who knows everything, who sees further than the rest of us, who walks into the meeting like a prophet and drops solutions on the table. It’s a comforting fantasy, especially when the stakes are high. But in practice, this kind of leader becomes a bottleneck. They kill collaboration. They build teams that are afraid to speak up, afraid to ask questions, and worst of all, afraid to think. The moment people on your team start believing that their value lies in saying nothing and deferring to the person in charge, you’ve lost.

I used to feel that pressure too, like my credibility depended on always having the one right answer locked and loaded at all times. But pretending to know everything doesn’t make you more credible. It makes you brittle. And brittle things tend to break when real pressure hits. Overconfidence in leadership, according to Entrepreneur, especially during crises, “can cross the line into the danger zone,” where authenticity gives way to ego and collaboration goes to die.

Over time, I’ve come to believe that one of the most important things a leader can say is, “I don’t know, but let’s find out.” Not as an escape hatch, but as an invitation. It tells the team that they’re allowed not to know either. It invites curiosity. It tells people that we’re here to learn together, and that finding the right answer is a shared responsibility, not a solo act for the boss. And weirdly enough, research backs this up. A recent meta-analysis found that when leaders express uncertainty instead of faking confidence, people actually trust them more and think they’re more competent. It’s one of those satisfying little paradoxes: the moment you stop pretending you’ve got it all figured out is the moment people start believing in you.

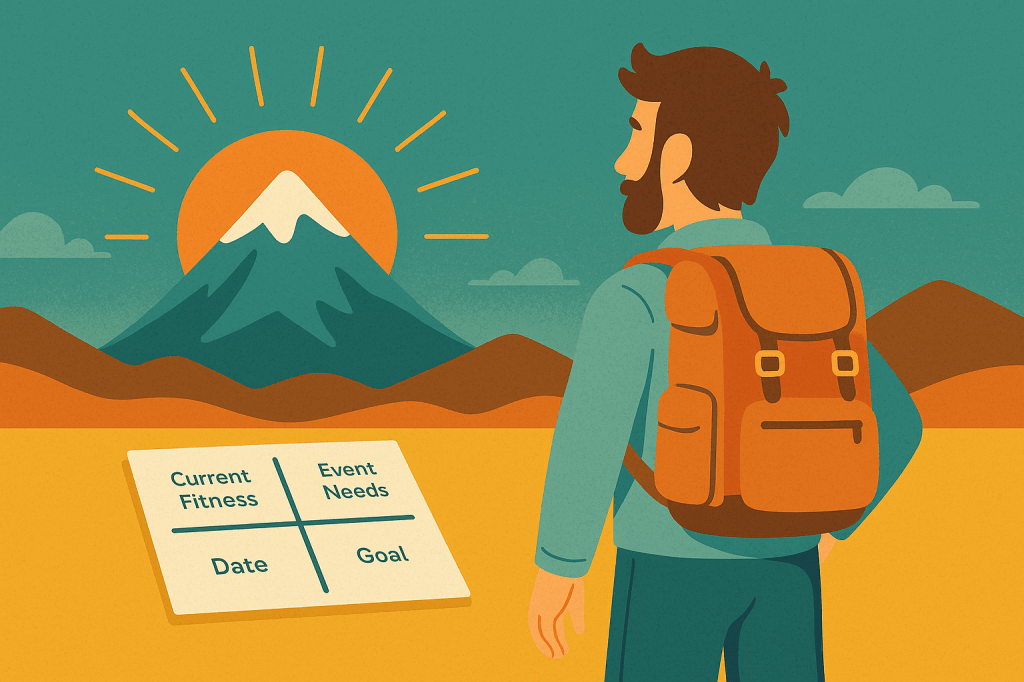

But if your default mode is always to have the answer, whether you actually do or not, you’re going to train your team into silence. And worse, you’re going to stop learning. One of the easiest traps to fall into is mistaking your authority for omniscience. But leadership isn’t about being the smartest person in the room. It’s about making sure the smartest ideas in the room have space to be heard. In my case, that often means handing the question off to someone who’s seen more edge cases, who’s driven more miles, who’s figured out a solution to that weird glitch I’ve never seen. I’d rather point someone to the best resource than try to impress them with some half-informed answer. That’s not humility for its own sake–it’s efficiency.

There’s a popular quote from Google’s Project Aristotle research that’s showing up in a lot of leadership seminars lately: the single most important factor in high-performing teams is psychological safety, which is the basic idea that people do their best work when they know they won’t be shut down, shamed, or penalized for speaking honestly, taking risks, or owning up to mistakes. And nothing destroys psychological safety faster than a leader who punishes questions, shuts down feedback, or reacts defensively to being challenged. Those leaders don’t build strong teams. They build echo chambers. And echo chambers can be quiet, not because everything’s working, but because no one’s talking anymore.

I’ve seen both kinds of leadership up close. I’ve had bosses who responded to every issue with a kind of rehearsed confidence. I even had one boss whose philosophy was, “Never let them see you sweat.” And I’ve had leaders who said, “That’s a great question. Let’s think through it.” The difference in team culture was night and day. One team was rigid and anxious, always waiting to be told what to do. The other was flexible, collaborative, and surprisingly resilient under pressure. The second team didn’t succeed because the leader had all the answers. We succeeded because the leader made space for us to ask the right questions.

That’s how I try to approach my own leadership now. I still prepare. I still try to be informed. But I don’t cling to the illusion that I’m supposed to know everything. I tell people what I know, I share what I’ve seen, and I point them to better experts when needed. I treat questions not as tests of my competence, but as chances to model how we figure things out. And when someone brings something to my attention that I hadn’t thought of? I thank them. Because that’s what we’re here to do–build something smarter than any one person could build on their own.

Leadership isn’t about having all the answers. It’s about guiding people through complexity without pretending the path is always obvious. It’s about saying “Let’s figure this out together” and meaning it. Because the moment you stop pretending to be the answer key is the moment your team finally gets permission to start solving problems with you.