The new Toxic Avenger is gross, hilarious, and surprisingly sharp. It’s the kind of movie that sprays you in the face with radioactive sludge, then slips a genuine insight into your open mouth before you realize what’s happening. Beneath the gore and fart jokes is a strange but undeniable lesson in leadership, the sort of thing that sneaks up on you while you’re trying not to gag. It makes sense, really—leadership often comes out of the most uncomfortable circumstances. Few people ask to be in charge. Sometimes you just fall into the vat.

Our unlikely hero is Winston Gooze, a janitor stuck at the bottom of the ladder, ignored by his employers, crushed under the weight of medical bills, and dismissed by nearly everyone around him. His life is a quiet humiliation until one day, fate dunks him headfirst into toxic waste. When he emerges, he’s mutated beyond recognition, but more importantly, he’s transformed into someone who refuses to be stepped on again. That’s the thing about leadership—it doesn’t always sprout from ambition. More often, it comes from necessity, when the alternative is to remain voiceless while everything collapses. James MacGregor Burns built the foundation of transformational leadership theory on this idea: leaders and followers rise together in moments of crisis, elevating each other to a higher level of motivation and morality. Winston doesn’t want power, but suddenly the people around him need someone who can stand up to forces too big for them. Leadership in that moment isn’t a choice; it’s survival.

The villains in this story are bigger than a single person. Sure, Bob Garbinger is a cackling pharmaceutical CEO who checks every box on the “corporate monster” list, but the real enemy is the system he represents. This is leadership as resistance, where the role isn’t to fine-tune what exists but to smash it and rebuild something better. That aligns with Robert Greenleaf’s Servant Leadership, which puts the focus not on authority but on serving the most vulnerable. Winston’s mutated strength doesn’t make him a leader; his willingness to wield it for others does. Servant leadership isn’t soft. It looks soft right up until it swings a mop through the chest of systemic exploitation. It’s the same principle every decent Game Master eventually learns at the table: you don’t step in to hog the spotlight. You step in when one player’s antics are drowning everyone else, because your responsibility is to keep the game fun for the whole group. Winston’s grotesque vigilante justice is the same move, except with higher stakes and way more exploding heads.

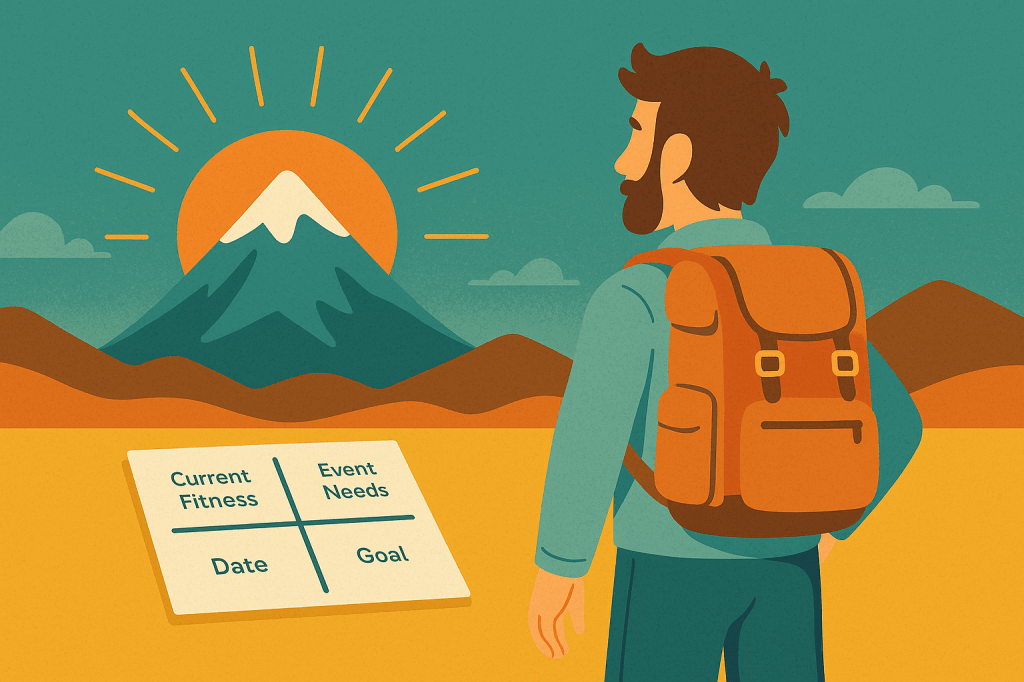

Winston’s fight isn’t driven solely by rage against corporate cruelty. At the core of his transformation is Wade, his stepson. That personal connection grounds his choices and gives his violence a direction. This is where Bill George’s Authentic Leadership comes into play: true leaders act out of self-awareness and purpose, not just raw instinct. Winston knows who he’s fighting for, and that clarity shapes his every grotesque decision. In leadership, authenticity doesn’t always look polished. Sometimes it looks angry, messy, and inconvenient. But people rally to it because it’s real. That’s the same shift every new supervisor goes through when they stop imitating their last boss and start trusting their own instincts. It’s the same shift GMs make when they finally drop the Matt Mercer impersonation and start leaning into their own strange rhythm. People respond to honesty, even when it comes wrapped in boils.

The film itself plays out like an ode to Situational Leadership. There’s no clean progression, no consistent tone, no adherence to the rules of superhero storytelling. One moment it’s gore, the next it’s satire, the next it’s slapstick. Winston doesn’t lead with a five-year plan; he leads by improvising in chaos. Paul Hersey and Ken Blanchard argued that leaders have to adjust their style based on the situation and the readiness of their followers. That’s exactly what’s happening here. Winston doesn’t get to stick to one mode of leadership. He mutates with the circumstances, whether that means bashing through enemies or offering a moment of protection to Wade. Anyone who’s ever tried to run a D&D campaign where the players ignore your plot hooks, bribe the villain instead of fighting him, and then insist on adopting the dragon knows this feeling. Sometimes leadership is just keeping the story moving when everything goes sideways.

By the end, Winston becomes more than just a mutated janitor with a vendetta. He turns into a symbol, whether he likes it or not. People rally around him not because he’s perfect, but because he embodies what they’ve been too powerless to say out loud. That’s culture-building leadership, where a person stops being just an individual and starts representing a larger identity. Organizations do this all the time, spinning origin myths and rallying stories to keep people connected. Tabletop groups do it too. Every party has a “remember when” story—the botched heist, the critical fail that almost wiped the team, the one perfect joke that still gets repeated years later. Those stories weld people together, even if the moment itself was a disaster. Winston becomes that story for the people around him, a reminder that resistance is possible even when the odds are grotesquely stacked.

What makes The Toxic Avenger stick isn’t that it offers a neat leadership model wrapped up with a bow. It’s that it acknowledges leadership doesn’t come from clean, comfortable places. It comes from desperation, from injustice, from pain. The leaders who matter most are rarely the ones who set out to be in charge. They’re the ones who decided they couldn’t keep going the way things were. Winston Gooze becomes a leader not because he wanted glory, but because he couldn’t bear to see his stepson’s future swallowed by corporate rot. And in that messy, chaotic decision, he finds a kind of power no boardroom seminar could manufacture.

So maybe leadership isn’t about polished presentations or carefully curated strategies. Maybe it’s about what you do when you’ve been shoved into the sludge. The question isn’t whether you come out clean—nobody does. The question is whether you come out willing to fight for the people who need you most.