Nothing makes people question your leadership faster than realizing the finish line they’ve been running toward just got picked up and moved. This is the organizational version of telling a kid they can have dessert if they finish their vegetables, then halfway through the broccoli deciding they also need to clean the garage and mow the lawn first. The dessert was never the point. The goal was to keep them occupied until you could figure out how to get out of your own chores.

In corporate life, this usually shows up when leadership makes a promise they didn’t fully think through. The intent might have even been noble at first — “Hey, we’ll make sure everyone gets a fair shot at promotion.” But when the sign-up sheet fills faster than expected and the people who actually have to conduct those evaluations start sweating about their workload, suddenly there’s a brand-new hoop to jump through. A leadership assessment. A timed test. An extra round of manager sign-off. And here’s the kicker: fail that extra hoop and you don’t just miss your shot — you don’t even get told what you did wrong, so you can fix it next time.

From the outside, this reads less like “streamlining the process” and more like “we realized how much work this would be for us, so we invented a filter to thin the herd.” There’s no transparency, no feedback, and no sense that the people in charge remember they promised you something in the first place. Which brings us to the real damage: it’s not the inconvenience that kills morale. It’s the unspoken message that your leadership’s word is provisional. Conditional. Entirely dependent on whether it still suits them to keep it.

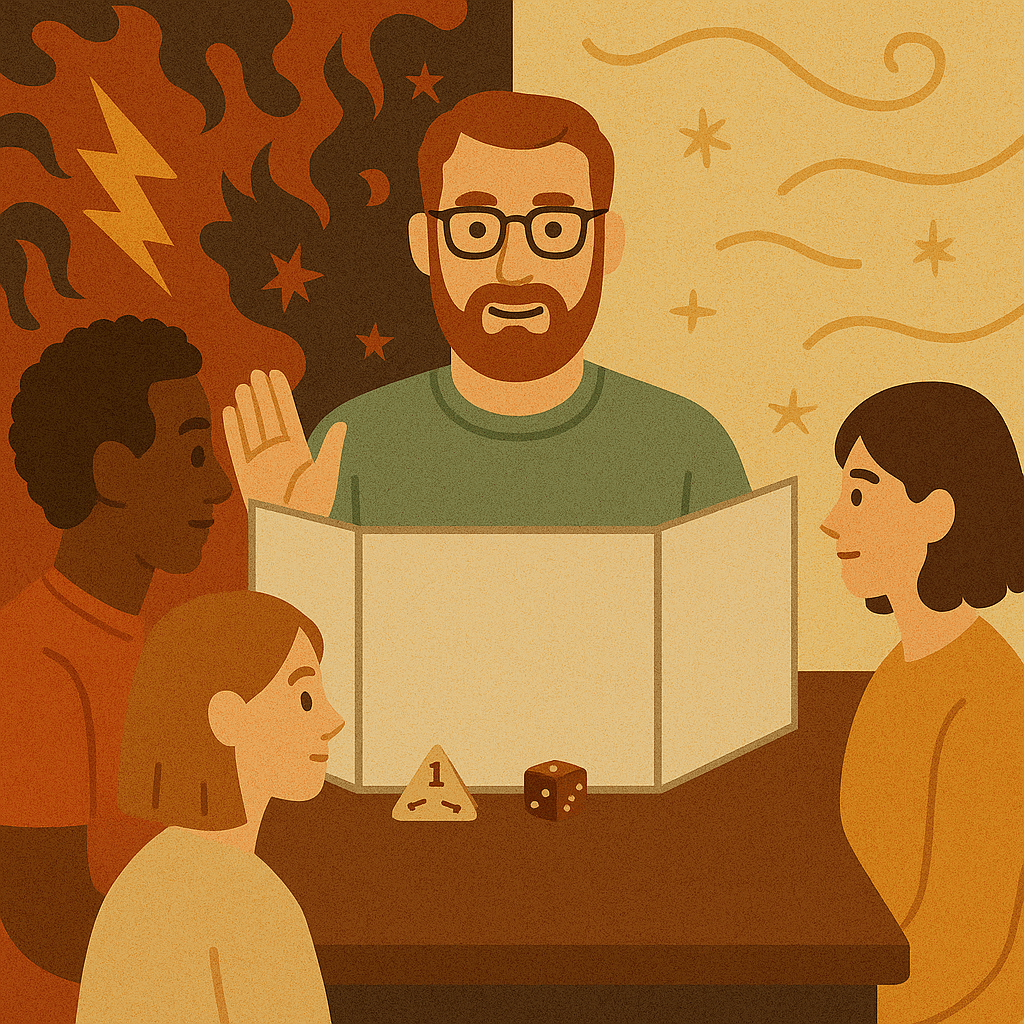

If you’ve ever run a game of D&D, you know exactly how this plays out. You tell your group that if they defeat the Big Bad Evil Guy, they’ll hit Level 10. This is the campaign’s driving goal. Every plan, every detour, every questionable alliance with shady NPCs is about gearing up for that final fight. Then, right before the big showdown, you say, “Actually, before you can fight him, you’ll need to pass this riddle challenge. Fail, and you can’t try again until next year. Oh, and I won’t tell you what answers you got wrong.” At best, the players feel blindsided. At worst, they start suspecting you never really wanted them to succeed in the first place. And once players stop trusting their GM, the game stops being fun. They’ll still show up — sunk-cost fallacy is a hell of a drug — but the spark’s gone.

And here’s where leadership theory has been screaming warnings for decades. In transformational leadership, one of the core jobs of a leader is to inspire people toward a shared vision through consistency, trust, and integrity (Bass, 1990). If the vision changes, you bring your team along for the why, the how, and the what’s-next. But if you just quietly rewrite the playbook mid-season without telling anyone, you’ve broken what Rousseau (1995) calls the psychological contract — that unspoken agreement between leader and team about what each side owes the other. Once that’s broken, even the most committed, high-performing people start conserving their energy. Not out of spite, but out of survival. They’ve learned the rules can change without warning, so why go all-in?

There’s a way to fix this without torching morale, but it requires humility and a little bit of courage. If you truly can’t honor the original path you laid out — whether because of volume, budget, or your own failure to anticipate demand — transparency is your only way out. Spell out what’s changing, why it’s changing, and how people can still succeed under the new system. Give feedback, even if it’s just “You scored lower on decision-making under time pressure — here’s where to practice.” If you have to thin the candidate pool, do it in a way that still respects the original promise, even if it means spreading things out over a longer timeline. Otherwise, you’re just selecting for the people most willing to tolerate frustration, which is not the same as selecting for the people most capable of leading.

The rules can change — life’s unpredictable, and leadership is about adapting. But if you want your people to keep showing up with full effort, the one rule that can’t change is this: when you say something matters, it has to keep mattering, even when it’s inconvenient for you.

References:

Bass, B. M. (1990). From transactional to transformational leadership: Learning to share the vision. Organizational Dynamics, 18(3), 19–31.

Rousseau, D. M. (1995). Psychological contracts in organizations: Understanding written and unwritten agreements. Sage Publications.